Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

Lindsey French’s Passive Protagonist

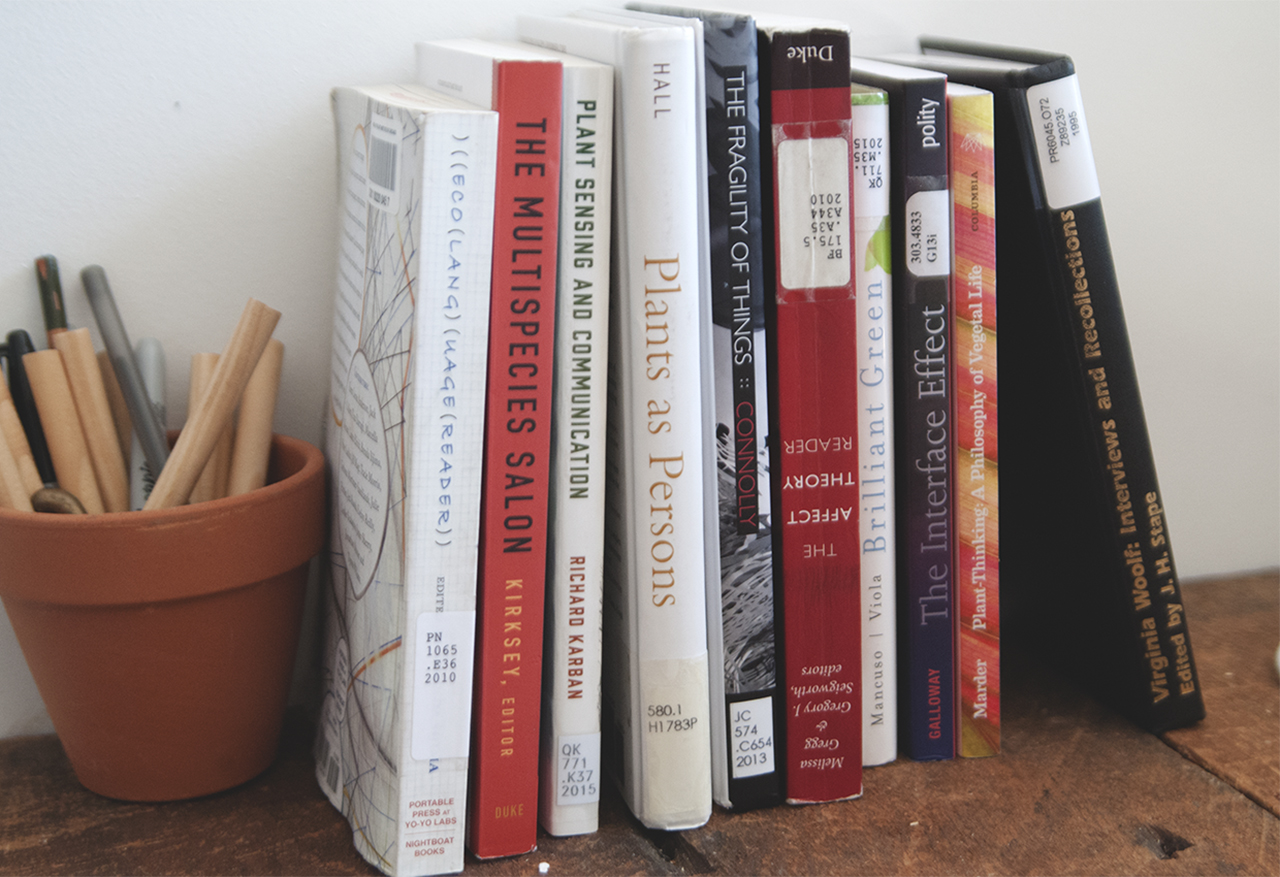

Researching ways to interact with plants on their own terms, Lindsey has hosted a symphony for plants by plants, introduced herself to poison ivy’s infectious chemical, and dedicated herself to experiencing the world in the same ways as the peripheral life form. Through these experiments and projects Lindsey aims to understand plants’ quiet role outside of the perceived center, appreciating each for their often passive existence rather than forcing an aggressive examination of their delicate form.

I\W: Why are you interested in exploring a phytocentric perspective?

LF: I think it probably first started when I was a little kid. I wouldn’t try to be a plant per say, but I would try to be really invisible and remain in the background in my household of a large family. It wasn’t until 2012 that I started working with plants in my practice. I have a background in landscape studies and looking critically at the landscape, kind of like an art historian would look at paintings or works of art. Landscape studies looks at landscapes to understand social culture in terms of an ecological perspective. I held a concert for plants, by plants in 2012 which was one of my first plant investigations. I invited people to bring their houseplants as guests to a concert in Chicago where the performer was a cherry tree that lived in western Massachusetts. The tree had a little piezoelectric disc, a vibration sensor, that was hooked up to the internet. Through this process those vibrations on the cherry tree were played through a material for Chicago plants so they could feel in real time these vibrations from the cherry tree. For me it was this move to try to focus on plants and try to think about what a plant is feeling or experiencing. I just acted as a facilitator. It wasn’t about me and my experience up front, but positioning me and the human audience as assistants for these plants to have an experience of their own.

Why is this communication with plants important to you? How does that translate to a larger perspective?

I think generally the place I am working from, or the larger social and ecological perspective, is a lot about climate changes or other conditions that ask us to think about precarity. That can be something that is really scary, but I like to think about the ways that we theorize about plants. There is something calm or potent about how a plant approaches these things. It’s distributed, it can lose parts of itself, it operates on vastly different time frames. It is very weak in some ways. A lot of approaches to solutions are about strength and action and I feel like there is something more interesting in a weak or inactive approach. Plants have more room for listening and responding rather than acting out of fear or apprehension.

How does that communication with plants change your mind about communication in general? You are working with this communication that is far more one-sided and not very cohesive.

Actually it has altered it pretty significantly. When I learned about communication in general it was usually explained that one-to-one communication is expressed through words and body language. You must have an intention and meaning. With plants it is this passive thing, there is not necessarily an intended receiver, but it’s not to say that there is not intention in that sort of signaling either. Being present in the same space can be a form of communication, or where you position your body, or listening can also be a really valid form of communication. It has made me think more about what’s carrying the meaning from one place to the other. Human communication is language or words or voice or sometimes body language, but looking at biological communication has opened it up for me to understand that a chemical action can be a communication—something that is not even visible or perceptible to me.

Can you talk about your experimental communication with poison ivy in some alteration of the one that feels?

I feel like up until last fall I had been working with plants in a way that was really safe and a way that was noninvasive and trying to be really respectful. It felt like there was moments where I was instrumentalizing these plants, and of course there is not really any way of knowing if there is a form of collaboration happening, or more importantly if I am representing that plant in a way that is respectful. I was at a conference panel on pain and communication, and I was struck by the idea that with pain there is this intense communication happening because something is at stake for those involved. Somehow over the course of the next few days I realized that a way to put me into communication with a plant was not to reach out and have this plant come into my form of communication, but actually try to put myself into their form of communication. I started spending time with a poison ivy plant and at first I was really cautious, using gloves and washing my hands, but eventually I lost these measures of protection and became more reckless, allowing skin contact but also allowing the urushiol (the chemical many of us are allergic to) to permeate my skin and cause a reaction. It was a way to explore these ideas of intimacy with this kind of other, this unknown. I think in some ways it is a way of thinking about fears of intimacy and the discourse around intimacy with any other.

What is the sensual nature of communicating with plants?

I think that word ‘sensual’ is interesting because if you think about it we put it in this romantic context because in romantic relationships that is a way that we can extend communication. But also at a base it is about sense and different kinds of perceptions. I have noticed in these different impossible ways of trying to communicate with different plants or organisms, that in order to get to that language, one of the ways is through sense rather than a meta or linguistic method. Can I touch this? But I’m not interested in turning the plant into an instrument to amplify my touch. There is not a lot of feedback from the organism about whether or not that is consensual. I guess with a sensual approach I also feel something back. So a lot of the gestures end up being quiet or sensual in that there is a focus on touch or scent or something that is much more ephemeral, and I have to cultivate being receptive to quiet responses. Sensual is all about the senses.

I also want to acknowledge my own otherness or inaccessibility — the parts of my identity that are marginal and want to stay there. I won’t always be able to perform a clear identity, or be heard or even seen. And I like that. There’s a lot of flexibility in it.

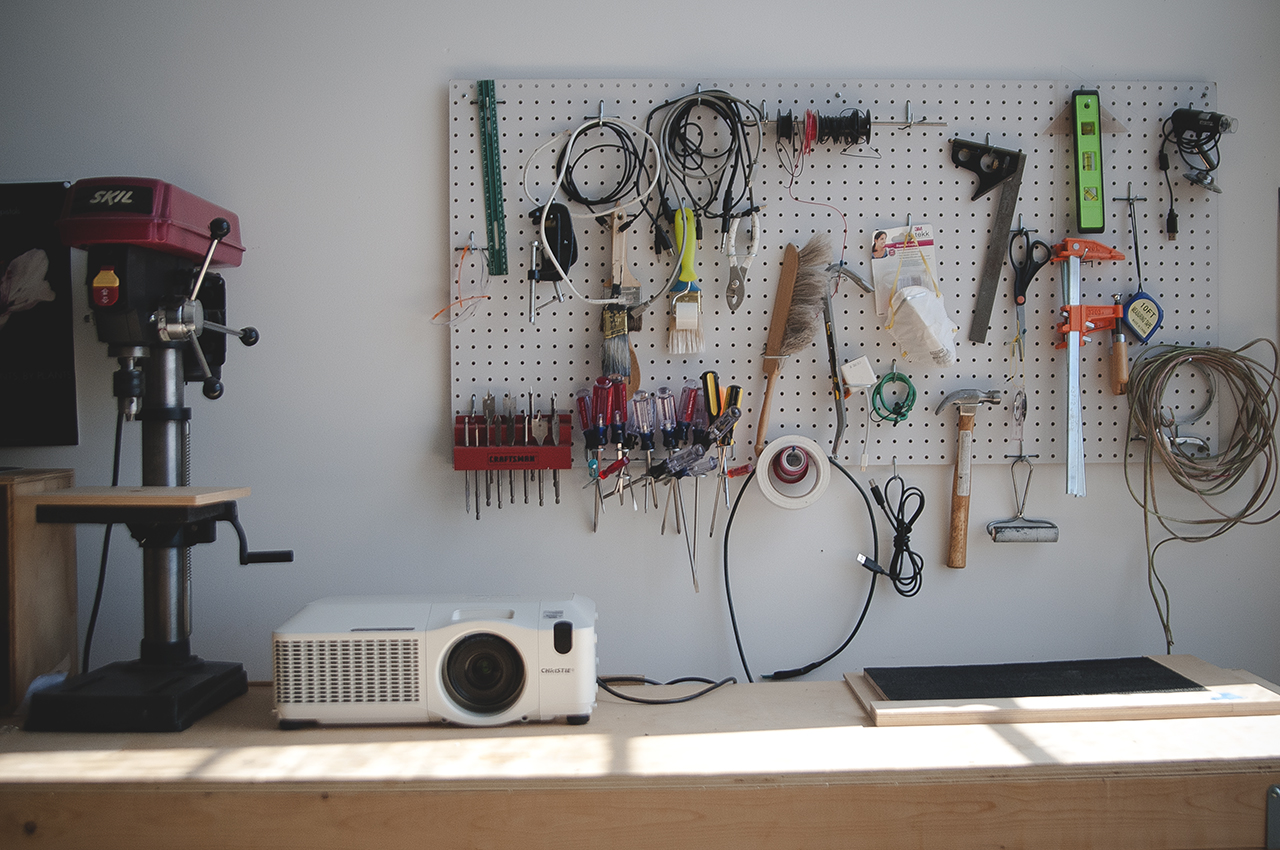

How are you incorporating technology into your practice to make this communication with plants more contemporary or accessible?

My MFA is in Art and Technology Studies and sometimes I feel like there is this expectation that every project has a very specific type of technological media, but mostly I think of the technology as a mediation tool. For me it allows a kind of extension of myself by providing a meeting ground. The technology is this channel for those involved to interact. I guess more broadly I think about the metaphors that we use to understand technology often come from these plant or vegetal sources, like how internet culture is described as rhizomatic, or its structure described in terms of how mycelial networks operate. This kind of language lets us think of the internet as this natural thing, for better or worse, and even though these metaphors don’t really hold up and are entangled in cybernetics they can still open up weird ways of working, especially when they fall apart. I have been working on a fictional grass called packet switchgrass, which refigures early internet history in terms of vegetal agency. The story of the internet is often told with the intense rhetoric of democracy and ingenuity, usually highlighting this military history. But it was also happening at a time of flower power and grassroots anti-war protests and plants asserting a role in this cultural conversation.

Do you feel like you are advocating for plants in pieces like Phytovision that give the viewer an understanding of how a plant might view very human activity?

I gave a talk last weekend where I reconsidered this word “phytocentrism.” Partly the initial or simpler goal of that is to take a media that we are all using anyways, like a screen-based media, and then reformat it so it puts us in the perspective of the plant. What would a plant see in these situations? There are some studies that say most plants perceive light and shadows, but also certain colors like red and blue. The Phytovision series was retrofitting certain films or videos or other kinds of experiences for that plant perspective. Some versions of it are for plants to watch and take in these different colored lights and others there is this human standby that has to turn it on. As the human you get this experience that is not familiar to you. I feel like I still have a lot of work to do in those terms. It is more about destabilizing our perspective and considering a different position. Part of the questions of this work is in validating these ways of being that are marginal or peripheral, and maybe that is the main cast of all of my work. So to ask for this “phytocentric” perspective is to put the plant in the center. Maybe it’s not about putting a plant in the center, but noticing its marginality and saying that’s OK, and noticing my own marginality and also saying that’s OK. I don’t have to move to the center, or make a new center—there are ways to relate to the plant on its own terms. In this way I also want to acknowledge my own otherness or inaccessibility — the parts of my identity that are marginal and want to stay there. I won’t always be able to perform a clear identity, or be heard or even seen. And I like that. There’s a lot of flexibility in it.