Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

Maria Gaspar: Articulating the Unknown

Founder of the 96 Acres Project, Maria works alongside a group of community members to produce alternative narratives tied to mass incarceration at Chicago’s Cook County Jail. Drawn to issues such as the displacement and immobility of incarcerated individuals, Maria works closely with audio to create spaces of visibility in both her personal and community-based practices. Often working outside of the studio, Maria improvises and devises creative meeting spaces for her projects in churches, empty storefronts, and front yards.

I\W: How did your personal practice move into a more community-based practice? Is this a thread that has always found its way into your work?

MG: I have had a public art practice rooted in community-based art since I was in high school. I grew up in Chicago and started creating murals when I was 14. So for me, that was a big part of my life and identity as an artist. That was also a large part of my art education, especially in thinking about transforming public space, power, and geography, but also using improvisation and community-based practices as generative ways of working. I find that work to be deeply personal. Throughout my grad and even undergrad studies, I felt as if I was leading a double life. I was making studio projects that were located within formal art institutions, and felt as if I hadn’t quite figured out how to articulate the threads between that work and my public, community-based art projects. I was making these large-scale public art projects, but then also making weird looking brown blobs in my studio. The breaking point for me was when I was doing a massive mosaic mural as part of a youth arts organization in Chicago. I was working with over fifty young people on a 1600 square feet mural made of Italian glass tile. Although I loved the experience of working collectively, the project started to feel merely decorative to me. It felt like the project was being whittled down to something that at its core wasn’t as radical as I wanted it to be. This was a profound moment that helped to define the kind of work I wanted to make, and one that intersects between various modes of working.

I\W: Is this when you began to work more more performatively, initiating projects such as City as Site?

Yes, I was exploring performance through solo projects already, and wanted to engage issues of performance in my community work. I knew that was exactly what I wanted to be doing. I was interested in those same aspects of it being a public art practice that so many people fall in love with—the collective modes of working, improvisational processes, and working with both artists and non-artists. City as Site brought together ideas around public actions, performances, and theater, while also looking at landscape and place with youth from the local area. So that project was an exciting moment for me because it allowed me to bring all of those aspects together, ones that I enjoyed and were meaningful to me, while also grappling with spatial justice issues at the same time.

I\W: Why do you think you are so attracted to community-based projects?

Well, they have a long history in a place like Chicago. We are known for the first community-based mural, the Wall of Respect on the South Side, so I admire this legacy rooted in equality and civil rights. That history is important, but so is thinking about what projects are happening in Chicago right now. For me, artists are rabble rousers, interlocutors, and can be great interventionists. I think we are good at articulating unknowns and emotional experiences that are hard to put to language. Using performance, theatre, and sound to figure out and problem solve with public exchange became much more exciting for me as an artist. I also wanted to get other people excited about experimenting with a variety of creative approaches. That collective problem-solving and meaning-making is critical to a human experience and, for me, can catalyze a sense of liberation and freedom.

I\W: What are some of the core ideas that you and the other organizers of 96 Acres Project share? How much improvisation does the project take?

I was just talking to a musician friend of mine yesterday about improvisation. He is also a visual artist, and he was talking about how in music there are certain harmonies or structures that if the group doesn’t come with a set of understandings around, that the collective improvisation doesn’t work so well. So, when I think about the term improvisation, I think about how challenging it is, and try to come up with various ways of creating a generative situation to bring about compelling ideas. 96 Acres Project is now in its fourth year. I was born and raised a few blocks away from the jail, and witnessed its landscape while taking the #60 bus every week to and from school. I also visited the jail while in elementary school, and saw its impact on my neighbors. Many of the collaborators and participants from across the city have long-term relationships to the issues around mass incarceration, or are committed to social justice in their own fields and work. I think the politics of the body and the politics of place are ideas that are examined within our work. We like to think about questions like how do places of incarceration affect our psyches, our social and cultural relationships, and our political ideas? How does the physical space influence our social behavior, and how do we critically examine that? We have spent time discussing systemic oppression and how it plays a role in our everyday lives. The jail is the largest piece of architecture in the neighborhood. So for me at the outset of the project I was interested in that perceptual and political experience based in cultural understandings/misunderstandings about criminalization, policing, and surveillance. Rather than normalizing the jail, the project seeks to offer up and imagine new alternatives through art.

For me, artists are rabble rousers, interlocutors, and can be great interventionists. I think we are good at articulating unknowns and emotional experiences that are hard to put to language.

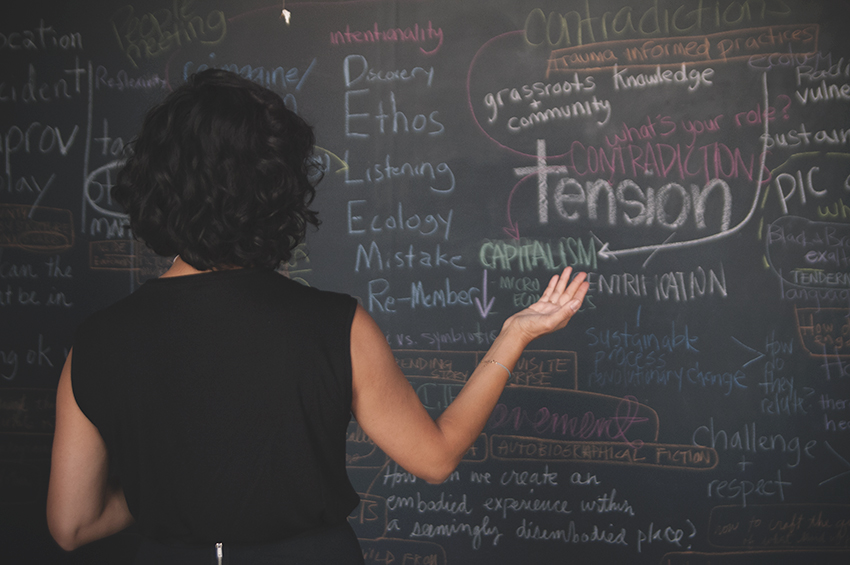

(Project Notes from 96 Acres Project Steering Committee Meetings)

I\W: The project began by engaging the voices that surround the jail, however you are now beginning to work with the voices inside. Can you talk about that move from the outside in?

The last four years have been really focused on mobilizing people on the outside, and for a long time there have been a lot of folks that have already been doing this work. All of us that are involved in the project—the teachers, the activists, the families, the neighbors—they all practice transformative justice on their own, and in different ways. They are teaching and asking questions about root causes in their classrooms and schools. Recently there was news about closing private prisons, and largely there is much more attention concerning issues of mass incarceration. How does police violence, anti-blackness, and the killing of black youth inform this project? And more recently, how do we respond to the rise of racist and xenophobic culture? There is a lot of reflection and relearning to do, especially at this critical time. It seems important that the next step would be to go inside with the folks who are currently incarcerated. Previously, we had collaborated with some community members that were formerly incarcerated, but now we are planning to provide creative opportunities to those inside. So, there is much to be figured out still and we are certain that the participants will be teaching us a lot throughout this process. The latest 96 Acres Project, RADIOACTIVE, will offer that opportunity by exploring audio workshops that include storytelling, sonic landscapes, fiction, and possibly a novella format project. The name RADIOACTIVE plays with the terms activism and action. The idea is that participants will be able to broadcast on the jail wall using that structure, the frame, and then hopefully dissolve the wall through audio and visual projects.

I\W: How do you highlight the voice of someone their audience can’t see?

As someone who is interested in performance and the politics of the body in space, I think a lot about how you embody an artwork, a set of issues, and how you engage others. How do you get others to get conflicted about something and negotiate it? Recently, I was talking to a theater artist friend of mine. We were having a discussion about audio, and his first impression was that audio is completely disembodied. Then we had this really beautiful discussion about how sound travels through the body. We spoke about the way it comes from the interior of the shell of ourselves and travels through the diaphragm and the chest, and comes out through the mouth. There is something really powerful about that because it is about voice, and to me I think about audio like a material. How does that then come into its own kind of space? If I think about issues of mobility and immobility, I am drawn to thinking also about forms of embodiment and disembodiment – who is mobile and who is immobile, when do we feel connected and located, and when do we feel disconnected or displaced? Using audio as a medium can get to some of those questions in interesting and, I hope, powerful ways. It can be incredibly personal and political at the same time. One can relate the idea of the voice to issues of power, and think about how silencing and invisibility both function. I am interested in how the recorded voice can create a space of visibility. I can’t really claim that I give others visibility, but I think that maybe what I can try to do is create situations within my own work and with others to present highly creative spaces where participants feel like they can be heard. And also, create a space where a public audience can listen and learn something new, or question their own misperceptions.

I\W: Do you consider this space your studio, or do you have a more broad understanding of what your studio is and where it can exist?

How is a studio defined? A studio is a laboratory and a place of experimentation. It is also a place of refuge. Sometimes the studio is a quiet space, I am by myself, I can be messy. I really honor the introspective qualities of a studio, but I also host meetings here, so it’s not always quiet! In fact, it’s also a place of exchange. I enjoy when physical spaces can be many things. Historically my projects have moved around all over the city. In the past, I have done work using empty storefronts, like the one that a local businessman let us use 10 years ago for the Little Village Arts Fest exhibits. I have also organized collective, public performances down main streets in Chicago. I like when a studio, a space for creative work, happens in unlikely places. I like when meetings take place at the local church or someone’s front yard. It is about work, and exchange, and creating thriving spaces wherever they may be.

I can’t really claim that I give others visibility, but I think that maybe what I can try to do is create situations within my own work and with others to present highly creative spaces where participants feel like they can be heard.

I\W: How has your community-based practice reflected back on what you are making personally?

It all feels personal, but I have been thinking a lot about all of the materials I have been collecting since I started the 96 Acres Project. Because I am also running the back end of things, there is just a lot of organization material that I have accumulated. I have been thinking about pedagogy and how that plays a role in a visual space. I feel like I have been contributing to a group and it has been exciting for me to do it in this collective space, but I am also giving myself the time to individually translate the experience. I think it’s about growing and challenging oneself on many levels. In the last 96 Acres Project exhibition at the Jane-Addams Hull House Museum, we exhibited audio that we had recorded as well as video documentaries of all the artists’ projects. I created a large hanging textile using a curtain tracking system. The image printed on the textile was a 10’ x 160’ image of the jail wall. I call that piece Haunting Raises Specters. I had been reading a lot at Avery Gordon’s work, a sociologist. The image of the jail wall was meant to be both haunting and compelling, especially in its scale. The piece was meant to be interactive, so that people could pull the wall away using the curtain track or even take the wall down. The textile was somewhat transparent so you didn’t know if you were on the “inside” or the “outside.” I wanted the thousands of viewers from all over the world that visited the Hull House to understand the project through a very physical, yet symbolic experience, especially if the viewer felt disconnected from the issues presented in the show. It was a way to implicate the viewer. What grew out of that piece then was a new sound project I worked on at a residency with the Experimental Sound Studio. I had been studying the informal architectures around the jail—the carnival, the Mexican Day Parade, and recording sounds from those events. The final piece is a composite of sounds from the inside and the outside, and then I made a video pan of the wall to go with it.