Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

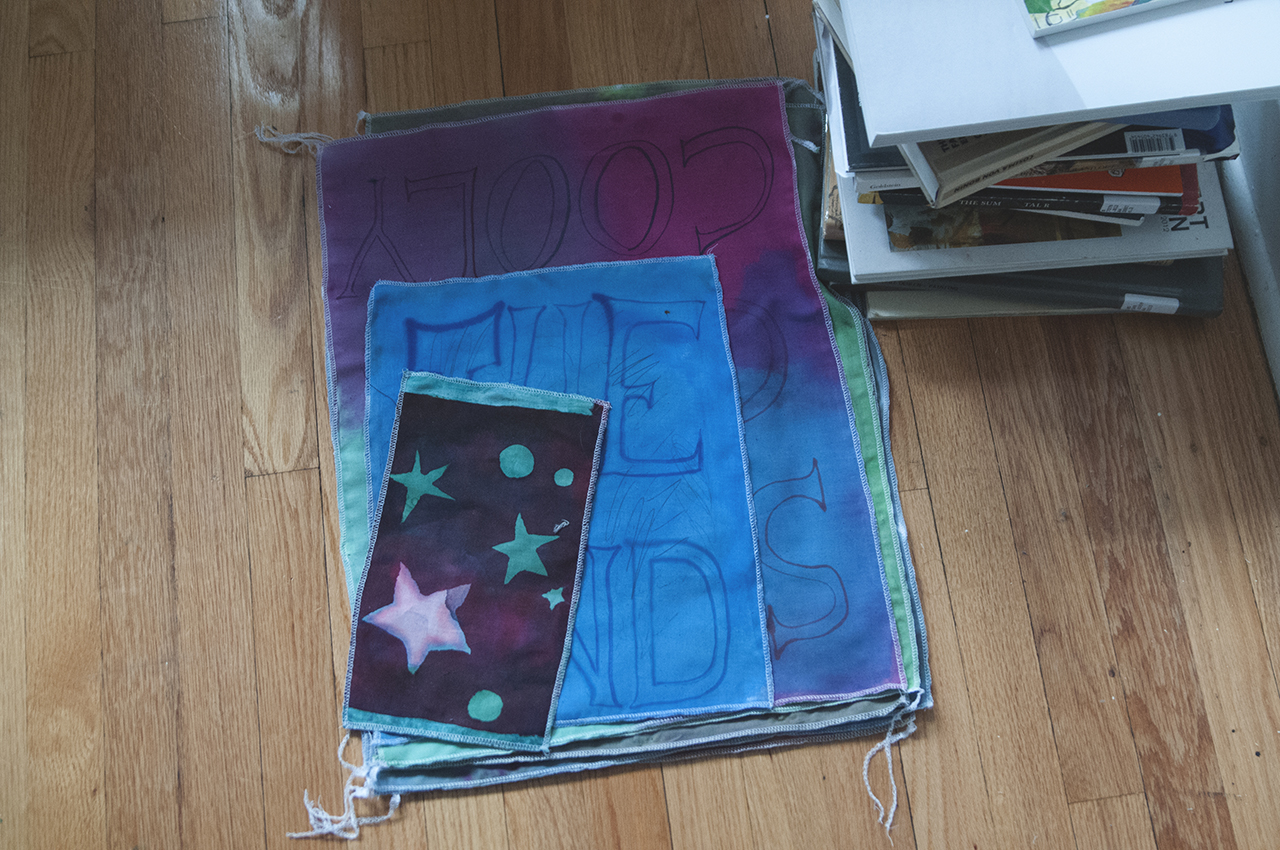

Cody Tumblin's Dyed Anti-Relics

Meticulously mixing dye like a mad scientist, Cody (who a plethora of beakers) uses the highly calculated process to paint onto cheap cloth. The material, which is often casually strewn around his studio, tends to be hung untraditionally after completion. Recently pieces were stretched into the shape of books from his personal collection as well as hung dangling from a laundry line. Paying attention to the personality of his materials Cody often sews pieces of fabric together to create one piece, using the seam as an opportunity to draw on his works.

I\W: How do you imitate a traditional painting process through dying?

CT: I own a lot of beakers and graduated volumes because when we were learning to dye in school we learned color mixing through very calculated measurements. It was a similar process to how a painter might learn to mix colors, except on extreme milliliter by milliliter variations. I would dye (usually plain cotton sheeting) a solid color, go back and bleach out certain areas, and then paint a new color or image in. I would attempt to imitate the standard masking and layering process of painting with dye, but I had to force the medium to an extent to get it to do what I wanted. These processes however, are really unpredictable and will throw you off nearly every time. It shares a lot of the properties of watercolor in the way that you can’t edit too much—you have to layer up a color or erase it completely.

When I first started painting, I was doing a lot of really calculated work and really mapping out where I would place imagery and color. I started to become tired of going to the studio because all of those steps and labor and measurements just hung over my head. I needed to approach my work in a way I could enjoy it again, so I decided to put a stop to all the planning.

How has that process transitioned into your work now?

I started revisiting old failed paintings and using them as a plan, painting on top of them onto another work stretched underneath, bleaching out portions and erasing my moves to create new problems. Now the majority of my studio time is spent just trying out things that I hope will lead to some small, strange discovery. It’s an ongoing cycle of stretching and unstretching, painting and cutting and sewing and usually throwing some of it in a pile for months. I just work until something happens that I feel satisfied with.

Ultimately, I just wanted to take more quick risks and think less about the outcome. And it’s been nice to feel resourceful. I’m finding new ways to constantly learn from the medium, but simultaneously trying not to understand it too much. Leaving room for a bit of mystery usually produces better results. I’d rather think of myself as a mad scientist than a boring artist.

Your research process involves a lot of collecting and archiving. How does that influence and translate into your visual work?

I definitely have a lot of avenues for where information I collect goes. I have talked to some artists who try to stay away from blogs and other painters as much as they can so they don’t get too influenced by it, but I am the complete opposite. I love absorbing anything and everything, from artwork to movies to books to video games to food. When I am looking at blogs and I see work I like, I will make a folder with the artist’s name and drag all of their work into it. I have hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of folders of artists and their work that I keep as an archive on my computer. As I am doing that, every one to three months I will simultaneously build an “idea” folder where I pull out images and pieces from the artists I have been saving, alongside lots of design and publication work, photographs—just whatever the hell looks good to me that I stumble upon. Sometimes when I am about to start new work, I will open a few of those idea folders and scan through them quickly to get my brain jump-started. It is definitely a part of my process that is maybe a bit of a mystery to me, but I really like absorbing imagery and seeing what comes out of it. It’s vital to how I function for sure.

During your show Tell Tale at Devening Projects you choose to have all of your works’ dimensions based off of books within your personal collection. Why did you seek to incorporate this personal element into your work?

It goes back to my passion of collecting. My wife Kayl and I love to collect artwork and books and vinyl. I would say that my library is one of my most passionate collections. I have always loved books and I feel drawn to the book as an object. Some of my favorites from my collection are Josh Smith books made from hundreds of Xeroxes of his drawings– faces and fish and leaves and lines, a few Tal R publications that are hand-printed with linocuts, a Gary Hume book I picked up in London of his floral paintings, an old Peter Doig “Young Man Goes West” with a bunch of his early cowboy-themed work that I also picked up in London, and a copy of Alice in Wonderland illustrated by Yayoi Kusama that is covered in polka dots (Kayl got this for Christmas last year). Each and every one has a nice objecthood to them—a character and personality through their textures, their imagery, the binding, the smell, the weight, the way the pages turn. And they each have a personal history of where I found them or what I was doing at the time I bought them. I thought it was a good starting point to the show, to start with something so personal. I knew I wanted to do a collection of lyrically placed small paintings, but I didn’t know where to start. I started measuring books from my library that I really loved, or books that I picked up often. It didn’t really have a huge conceptual weight, I just did it to get myself invested into something. You could draw parallels to literacy of image and some other personal connections to the work, which are good talking points or writing material, but I really don’t give a shit aside from it just being a fun starting place. None of that is too important to me. Sometimes the imagery in the book or the work of the artist would have a little bit of influence as to how I would start the painting or title it, but it didn’t really have a whole lot of weight in the creation of the work.

I like the work to hold the personality of the cloth, for the color and texture to have its own presence. There’s no mystery to what you’re looking at in some ways. I don’t need there to be too much illusion.

In what other ways have you messed with the traditional canvas?

Within the last few months I have been very attracted to oddly sized paintings. I like quirkiness and how something strange can speak to the audience a bit differently. I do like standard sizes and they are fun to work with, but they are so open-minded and generic that sometimes it is hard to really get into it from the get go. If I start with a certain strange size, you kind of know where you are going, you can predict its feel a bit. I am doing a two person show called Awkward Dimensions at LVL3 in August, and I am thinking that there might be some really weird long paintings and big loose fabric works—things that are kind of strange. I want to have my works intercept the space in a weird way. For my recent show at The Packing Plant in Nashville I hung unstretched paintings and studio scraps on clothing lines in the gallery as a kind of casual physical (and familiar to the home) approach the work, while embracing the space as a large collage of many overlapping works. Shows like these give me an opportunity to get weird, and I like a challenge to approach my work outside of a straightforward, institutional framework. Why not take a few paintings off the stretcher and stitch them together, bleach the whole thing out and drape them over a coat rack? More and more, I’m just trying to find ways to mediate my expectations and throw myself off balance. It may look like crap sometimes, but looking like crap is way more interesting to me than looking “good,” that’s for sure.

What interests you about working with such cheap material?

Fabric is just a great material to live with, to toss around, to fold up and sit on while you eat a piece of leftover pizza. One of my favorite paintings was draped over my studio chair for at least 2-3 months before I picked it up again. I’m pretty sure I’ve spit food onto it, splashed dye onto it, sneezed on it, walked on it, everything. I lived with it. A lot of my materials are on the floor and all over my studio. It is part of my surroundings, and they are not overly precious. A good friend of mine, Wyatt Grant, once told me “You can eat your lunch on it” when digging out a pile of old paintings and screenprints on fabric. That always really stuck with me, trying not to treat your work as a holy relic. When painters prime and gesso and sand a canvas down, they’re essentially preparing the work to become another kind of object other than cloth. I don’t like that. I like the work to hold the personality of the cloth, for the color and texture to have its own presence. There’s no mystery to what you’re looking at in some ways. I don’t need there to be too much illusion. Cutting and sewing my works has also helped mediate this, even if to nod at least a little bit to the material and say that these aren’t just paintings. When I think about making an image, I think about constructing an image physically and how you build up the layers, piece by piece. When I need to make a painting larger I just sew on a few new sides. I think of sewing as the same act as painting or drawing, it’s part of the image and how you carve into it. In some ways it will give me a structure to rely on, and in some ways it helps me break up the monotony of color and image and deconstruct its self-assuredness. Or just give me something else to do other than screw around with a brush.

Do you use the seam of your paintings as a way to incorporate drawing?

Definitely. I like the aesthetic of the seam, something about seeing the stitched line or the seam allowance or loose thread is such a common, everyday occurrence. People know it’s utilitarian in one sense, but familiar and attractive in other ways. I like it as an aesthetic decision, it brings a second look at the surface and at the makeup of the image. I like the accidents and the imperfections of the work a lot more than the original intentions. So, it has been fun to spend a long time on a painting and then take it off the stretcher and see a whole other world on the back of it, seeing how the dye gathers into a sewn line, or see where some colors didn’t quite make their way through the warp and weft of the fabric. The process of making is really what I care about. The act itself of creating is so much more important than the outcome.