Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

MuWDV: Devin Mays' Iconic Detritus

INSIDE\WITHIN and Danny Volk sit down with Devin Mays to talk about his work’s obsession with cigarette packaging, how religious imagery has found its way into his performative work, and Danny gets made up in the style of the Hughes Brothers’ film Dead Presidents.

Devin Mays: Danny, are you ready to get made up?

Made-Up w/ Danny Volk: Let’s do it.

INSIDE\WITHIN: What are some of the tenants of your practice that connect your photography, sculptural work, and painting?

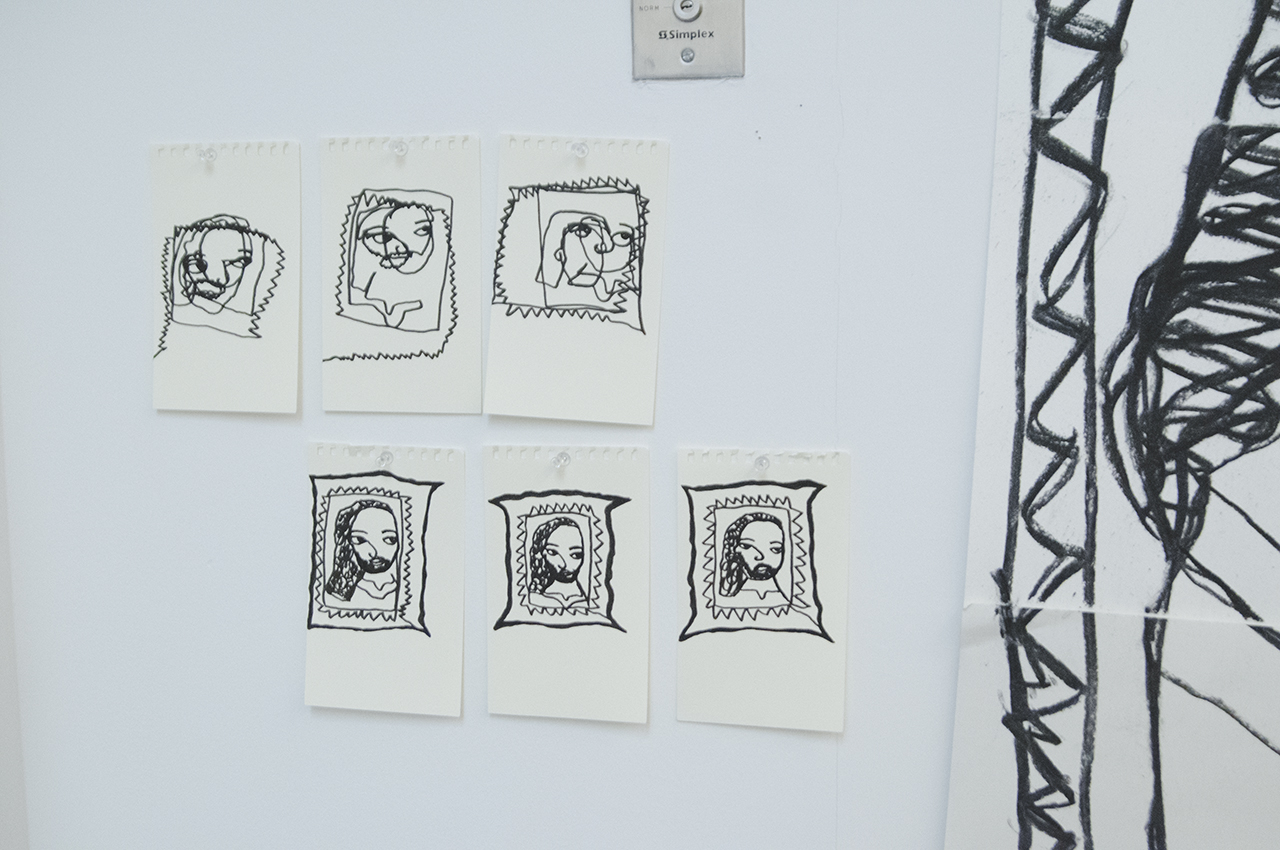

DM: For me, the idea of framing is what seems to be an ongoing part of my practice. How do frames work structurally? They crop, they add a center or a focus, and they create a boundary. I’m also looking at where frames are, how we see with them, how they hold imagery, and how they protect an image at the same time as they are restricting it. I think for me, that is kind of where the disparate parts of my practice overlap. Also seriality plays an important role in my practice. What does it mean to only make one object or image versus having two or three or more?

I\W: How are you moving away from editioned photographs and towards making unique sculptural works?

DM: Before I started grad school I worked in advertising for seven or eight years. When I first got to the University of Chicago, there was a need for me to create a distance from that background. I didn’t want that part of me to quickly take over my art practice that I was just getting to know. I wasn’t really interested in making editions. I like to think of photographs as just being objects, like a sculpture. I think it puts more pressure on me as a photographer to approach each photograph as a singular and autonomous object.

I\W: Have you migrated away from traditional photography completely?

DM: No, not completely. I’ve just become more thoughtful of its materiality. When I first decided to leave my more commercial practice, I really became interested in the traditional forms of photography. I learned that the material carried a baggage, which most materials do, but there were times when I didn’t want its historical background to limit my object’s functionality. Photography is a very powerful framing tool and because of its ubiquity I’ve become more careful of the where, why, and how I point the camera’s lens. I think that’s why I explored other modes of making. Plus, I wanted to implicate my body more in my work. And by using other modes of making, I think I actually appreciate the photograph a lot more. I interrogate it in a different way. Before, I would pick up the camera and then decide what to do next, now I let the idea lead me to the material, not the other way around.

I\W: What kind of subjects have you been investigating in your studio recently?

DM: Recently I have been thinking about material culture and iconographic imagery and its place in the world. I have also been thinking a lot about religion, hope, and how it functions within certain communities. I’m really interested in a physical and spiritual state of being in-between—a kind of horizontal and vertical relationship of being in-between. A couple of years ago I started doing what one might call land art, a Richard Long sort of thing, by incorporating a ritual of walking into my practice. Instead of creating an impression of a line during my walks, I found a preexisting one created by artifacts on the ground. I started collecting these artifacts and taking them back to my studio. It’s been an ongoing project that has evolved in many different forms: photography, sculpture, and performance.

I\W: What was the first way that you displayed the project physically?

DM: The first iteration was a photograph. At the time I was really into Anne Collier’s work. Her photographs of pop icons, magazine ads, and antiquated technology are gorgeous. I was thinking of those photographs when I was auditing the collected artifacts in my studio. I wanted to see what would happen if a Newport cigarette box or a bag of Flamin Hot Cheetos was handled with the similar kind of preciousness and turned into an iconographic image.

As a result, I created large scale black and white photographic prints with an inverse color relationship. What was dark became light, and what was light became dark, creating a large black field encompassing these found objects. I’ve titled this project Family. The latest iteration of the project has been more performance based and sculptural work. I’ve decided to focus my attention on the singular artifact of the discarded Newport box. It has an economy that interests me. In a recent exhibition I’ve taken discarded Newport boxes and placed them on opposite walls in the gallery. In a recent street performance I’ve blown up green balloons. I sat on the sidewalk on Cottage Grove in between the Green Line stop and 60th street and blew up a number of green balloons until I became exhausted. The color of the balloons are the same green Newport uses in their print advertising. That street performance is titled Pleasure and will be an ongoing experiment. It’s pretty amazing seeing what’s happened since I started only focusing on the Newport box. My colleagues have started sending me pictures of discarded Newport boxes, picking up discarded Newport boxes, and leaving them in my studio. It’s almost like these objects have become valuable. I’m sure most of them, including myself, at some point have ignored the discarded box. But now it’s no longer invisible. I don’t think they’ll ever look at the Newport box in the same way.

I\W: How does religion play into your practice?

DM: Religion, specifically Christianity, has found a way into my practice and made me think about how different forms of icon and religion operate. I think art and religion are these very weird distant cousins that are both faith-based practices. They both have their own lexicon and better practices, but specifically I am interested in how the icons of Christianity work. I grew up in a Christian household and I saw how having faith played an important role in my family’s life. I think about how religion plays an important role in the African American community. How hope and faith is an essential ingredient in transcendence and reaching a Promised Land. It seems that some communities have to deal, or choose to deal, with what seems like an infinite state of being in-between or waiting for arrival. I’m fascinated by this journey and I’m fascinated by the relics, performances, practices or representations of faith. You have this painting of Jesus behind me that I bought at a flea market in Detroit. It’s a really bizarre object. A brown skin man with long black wavy hair is tightly cropped in this ornate faux gold leaf frame. The cropping is so tight it almost cuts off parts of the man’s face and hair. Did someone make the frame or the picture first? Who is the manufacturer of this object? Someone decided to just pump out a bunch of copies and create this industry around religious iconographic works. The idea of industry there is interesting for me. There is an overlap for how I encounter the art world and what is being repackaged or sold. The tinting of the man in the picture, for me, also works as a metaphor for the tinting of this art market I choose to participate in.

Religion, specifically Christianity, has found a way into my practice and made me think about how different forms of icon and religion operate. I think art and religion are these very weird distant cousins that are both faith-based practices. They both have their own lexicon and better practices, but specifically I am interested in how the icons of Christianity work.

I\W: What does the clear plastic you use in a couple of your performance pieces serve as?

DM: The plastic I introduced as a protagonist in my work. The plastic was introduced when I went back to Detroit and bought the Jesus painting. It was wrapped in this ridiculously large plastic bag. I started thinking about the plastic that was being wrapped around other things and it as a material. I am interested in the currency that is associated with it. The frame can be contradictory to its usage. For me, plastic acts as this economical material that is supposed to protect other more valuable items. Then to a certain degree the plastic also cheapens the thing at the same time, like going to your grandmother’s house and seeing the couches covered in plastic. It looks ridiculous but it is interesting to me. It also has a memory. I try to use the same plastic every time. It is important that it is the same piece so you can see the traces of what has happened to it. There are little mushes of black eyed pea in there, some hair, a few footprints of mine—I like the idea that it is not forgiving. It remembers what happens to it. it is now a recurring character in my practice.

Recently I invited members of a church choir to sing in a gallery. The performance, Call and Response, started as I unwrapped the plastic around the hung picture of Jesus. Once unwrapped, I covered the gallery floor with the 100 ft plastic tarp. The choir sung a selection of songs as I laid down the plastic. Once laid on the floor they continued to sing on top of the plastic in front of the hung picture of Jesus. Because the choir members were standing behind a perpendicular wall in the middle of the gallery they could only be heard, not seen, from outside the gallery. It was beautiful. You could hear the singing in the basement of the building. Some people followed the singing until they found a small choir. Others I think were uncomfortable with the kind of singing and didn’t know if they should stay or leave. It was great to watch. I’m definitely going to work with that choir again.