Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

Diane Simpson's Detailed Continuity

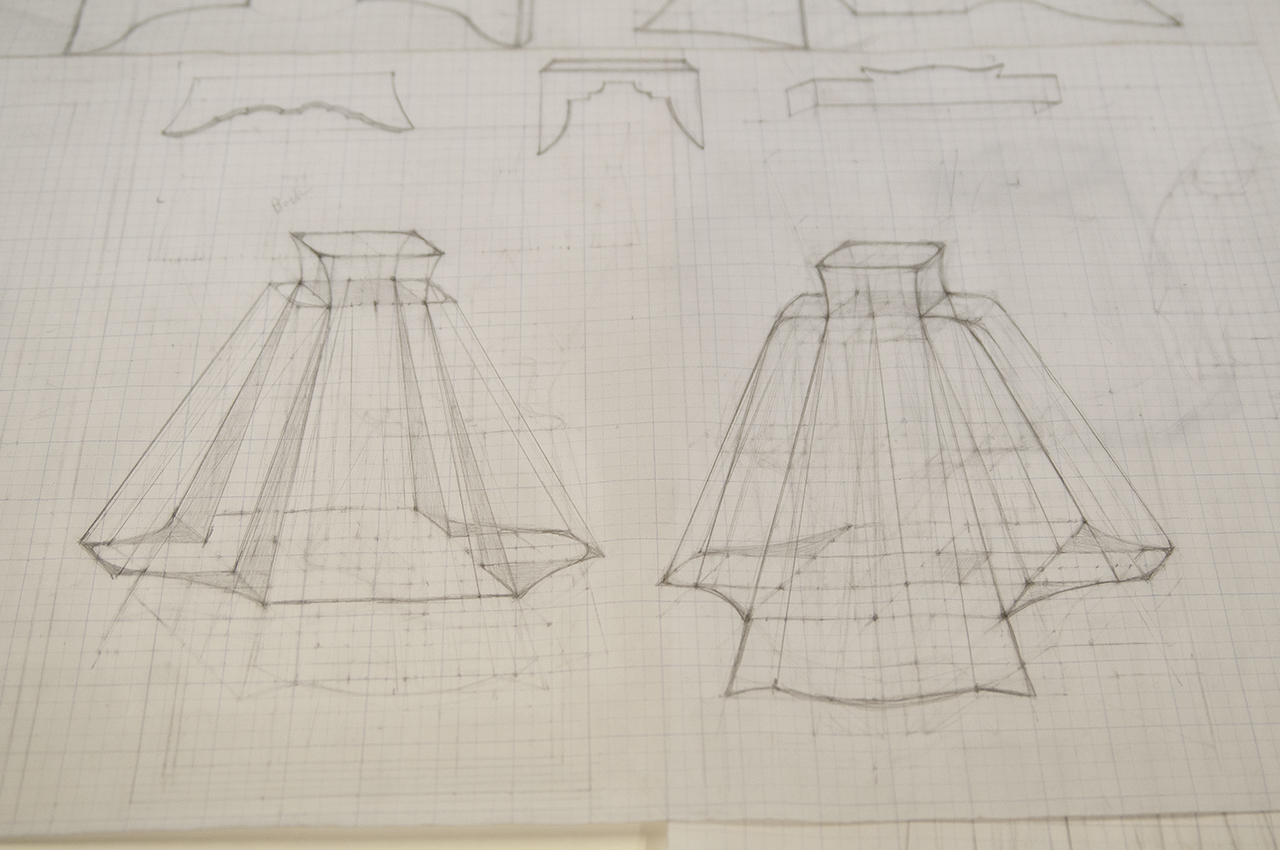

Working meticulously from drawing to model to sculpture, Diane creates objects that are imminently sturdy in both design and function. Leaving no detail unaddressed, works appear as comprehensive plans for future cities, with architecture forming one of Diane’s key inspirations. Although typically sparked by an item of clothing, the literal source immediately leaves Diane’s mind once pencil is to paper, letting the sculpture exist beyond the nomenclature of both architecture and fashion.

I\W: Do you aim at making the architectural inspirations for your works more domestic, or vice versa?

DS: I think they are almost equally important. My process begins with a visual source, often a two-dimensional photograph of a particular subject, and usually it’s something related to clothing, like you say, from the domestic world. Then I start drawing from that source and it morphs and becomes very removed. For some reason – it’s hard for me to even know why this is, but somehow, in the drawing process, the forms become more structural than they are to begin with. Initially, maybe I am just interested in clothing images that bring to mind certain architectural structures, so they are all intermingled. Also, I’ve had an interest from way back in a kind of naïve early form of perspective – using parallel planes to describe space rather than a two or three point vanishing point. I realized that I could describe an object much more easily this way, so that’s the system I’ve used to help me reinvent new forms from the original source. I want to be able to read clearly where I’m going with the sculpture, to be able to get details down before I even begin. Maybe because my background is in painting and drawing, I have never taken materials and just played with them. If I feel I have a good strong drawing – I depend on getting to that point before I even start in building the 3D version.

Do you ever deviate from that process?

Only recently, I’ve used an actual object as my starting point rather than a 2D source image. I’ve been collecting clothing items like bibs or collars that have interesting shapes. For a couple of sculptures, I started by tracing the shapes of the flattened collars and then enlarging them. I like getting away from a literal interpretation and I think changing the scale helps that. Then I transferred the shape to a piece of cardboard and just started to play with scoring and bending – with no predetermined form in mind. When I got the form I wanted, I transferred the form to a final material. I chose corrugated cardboard for one piece and the scoring and bending transferred easily to that material. Then I chose wood for another, so I had to find different solutions to achieve the same scoring and bending concept. It was about changing the flat shape to a 3D structure.

How long have you been focusing on designing bases into your work, rather than simply placing your sculptures on top of mass made ones?

Way back, I was creating large floor pieces so I didn’t really need to think of a base. Then I made smaller works, but they were suspended from the ceiling. Then around 2005 my interest was aprons and I wanted them to be free standing pieces. But the apron section didn’t extend to the floor. I had to design an extension which would serve as a base, but would be completely integrated with the rest of the apron—to be built and viewed as a unit. Another piece called “Bib Dots” had a different problem. It was too small to go directly on the floor, but it also didn’t work as a wall piece. I wanted it to be close to the wall, but also to have some space behind it. So I designed a shelf that related to the shape of that specific piece. I’ve done that for a few pieces now—having the shelf as much a part of the piece as the piece itself.

I really love your sculpture “Apron X.” Was that inspired by a more masculine fashion, like a butcher’s apron?

The source for that piece came from a book on vintage aprons. The photo was of an apron from the ’40s – a flouncy apron with big pockets on both sides. I think the reduced form and the materials I chose, transformed it into probably one of my more masculine pieces.

How do you create the dimensionality for objects that are seemingly lifeless, dress forms that are meant to come to life when placed on a body?

At some point in the drawing process, I usually forget that it is an article that would be worn on a human body. In fact at a certain point I forget about my source altogether. The drawing takes over. I’m thinking about relationships of the shape to the structure and pattern and how I am going to construct it. I’m not thinking about how it’s going to be worn; it is already a sculpture in my mind. I don’t want it literal, I am getting away from how it would conform to a real body.

You source your inspiration from all different time periods and movements that span the history of design. Do you think your final sculptures end up reflecting a similar time period, or have a certain sameness to them?

No, I am right there at that particular time with that source when I am doing it. It is nice to hear at times when people tell me that there is a thread going through my work, because I always wondered if my work is too diverse from piece to piece, especially because I use so many different materials. Most people work in a series and because they are working on more than one piece at a time, naturally it has this continuity; whereas I work on one at a time, then I start over from scratch on the drawing board again. I can see within a certain period that I am more interested in a certain shape or type of construction, but I just always wondered if a body of work I’m exhibiting might look like a group show.

What do you think might be an element that ties all your work together?

A lot of people have been interested in and spoken about my attention to detail; the sort of finish that is apparent in all the work. This is what might tie all the work together. I think I am obsessed with how every element of the piece has to be related. The details are not arbitrary, they are always dependent on the structure and the shape and the intrinsic quality of the particular material. I think I was very influenced early on in the 70s, when I discovered the German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher. They considered themselves architectural anthropologists. They were documenting these obsolete industrial structures. The point was that these were like anonymous sculptures were not designed by artists. They were designed by engineers, so there was no ego involved. It resulted in something that was purely functional, yet it ended up that the designs were very beautiful. It was form follows function. The reason that appealed to me so much was because of that interrelatedness.

Do you intend for your sculptures to be honest about their structure, function, and skeleton?

I think so. With my early sculptures, the individual sections were interlocked. They could be disassembled and they didn’t require any hardware. When I first started constructing them in a more permanent way, I connected the sections using dowels that you could clearly see – they were part of the piece. It bothered me to have any hidden hardware. That kind of thing is still important and when it’s possible continues to run through the work. But now I don’t feel too dishonest and guilty incorporating some hidden screws here and there—when necessary.

At some point in the drawing process, I usually forget that it is an article that would be worn on a human body. In fact at a certain point I forget about my source altogether. The drawing takes over.

Have you ever collaborated with an architect?

I have often gotten feedback from architects who find my work interesting, but I have never worked with one in terms of building anything. I create my work in such a crazy way. I love old architectural drawings but they don’t even do that now with all of the architectural programs on computers.

Were you surprised when people started showing interest in your drawings as works of art themselves?

I had a show with Phyllis Kind Gallery in ‘83 and I had working drawings for each of the sculptures in that show. Phyllis said they were too messy to exhibit, so I did them over neatly. They were completely lifeless. They were horrible. A couple of years later there was a group show at the State of Illinois building and the title of the show was Imagining Form, so it was sculptures along with their drawings or models. I showed these messy drawings, and there was so much interest in them. From there on if there is an opportunity, I like to exhibit the working drawings with the sculptures. Ideally I like somebody that acquires a sculpture of mine to have the drawing as well, but that doesn’t always work out. In fact, more people have my drawings than my sculptures.