Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

Sarah and Joseph Belknap's Celestial Synchronicity

Sarah and Joseph have created their own orbit at the far end of Chicago’s Pink Line. Looping effortlessly back and forth between their Cicero home and studio located in the backyard, the couple balance their love for 1000-year-old skulls and 1,000,000-year-old meteorites.

I\W: How do you balance your commercial and fine art?

SB: It’s a constant trial, and sometimes struggle. When we first started, we were in grad school and we were having one of those underground supper clubs at our house. The people that wanted to do it wanted to showcase artists, and we tried to inundate the house with art. We made all of these weird little sample pieces and threw them up all over the place. We liked them, but they had nothing to do with what we were interested in with art. They were fun to make. We started iamhome that way. It just kind of happened. When we started doing it, the purpose of it was to support our arts because grants are really hard to get. It’s been expanding so much that we do have to play between the two. The nice part is that we really don’t do anything else, so it gives us a lot of freedom. We are able to take a week off of the business if we need to focus on a show. It is a weird struggle that we have been going back and forth with. Not a bad struggle. iamhome is super fun for us because we get to play and make, and there is not a lot of concept or research involved.

JB: With iamhome it’s nice, because in fine art it is the labor of love and all of this thought, time, and turmoil goes into it. It is not commodity. It is very anti-commodity.

SB: Well not anti-commodity, just nobody wants to buy it. We’re not anti-commodity with it. We don’t try to make it to sell it. We started iamhome thinking about things that are kind of art, but more designed objects. Most of the things don’t have a necessary purpose, but you put it in your home because you like it which is really similar to our fine art practice. But as a designed object, it can exist just as what it is—this silly, funny thing that you can give to somebody.

Do you try to stay away from concept in most of your iamhome pieces?

SB: We don’t try to stay away from concept…

JB: They are just two different thought patterns.

SB: Yes, they are very very different. Part of iamhome is just being able to have fun. It’s a way for us to just screw around and make something. Just play to keep us active. We are both such makers that with our fine art, there is so much research involved. Sometimes you will research for a month and you are not touching as much as you want to.

JB: You might have an interest to do something, but it doesn’t fit into your practice. We like to dabble in things that broaden our language in how we can use things.

SB: With plastics, we started doing them for our business. After we were playing with them, the more we got to understand what their potential was.

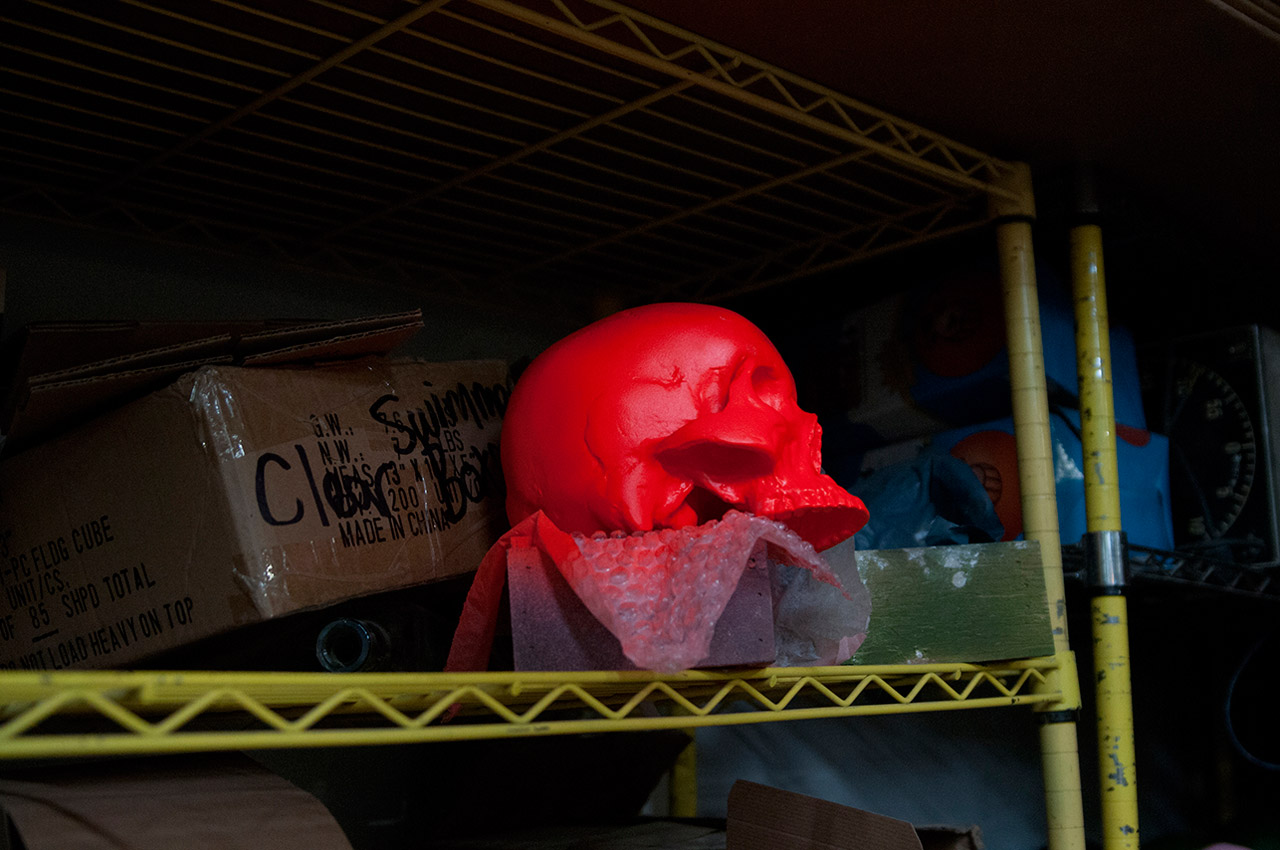

How do you mold your skulls for iamhome?

JB: We assemble the mold, strap it together, add the plastic component, then strap it into our machine and lock it in. With the plastic in there, it rotates the mold evenly so the plastic sets. How long we leave each mold in depends on several variables. It depends on the weather, when it gets cold in here we have to crank the heat up. My brother is a machinist in Philadelphia, so he actually manufactured the machine for us.

SB: We started putting them online and this anthropologist that teaches at Northeastern University, she contacted us and said “You guys aren’t being all gothy and scary about your skulls, do you want to borrow more skulls?” It was amazing. She lent us these skulls that are between 300 and 1000 dollars a piece so we can’t afford to buy them, but she just lends them to us as long as we make her one.

Is there one medium that you focus on more than the rest in your practice?

SB: We are really material based. We both have a really diverse practice. I did my undergrad in photography and fibers and Joseph did painting and sculpture and then when we combined, we went to school for performance art.

What type of materials are you working with currently?

SB: Right now we’re really into silicone and we are doing the moon skins. Anytime the moon is out we bring the telescope out and look at it for a little bit. We both try to remember what we saw, try to take a mental picture of it. We have four individual moon skins and then one big one. So each of the small ones I did one, he did another. We were looking at the exact same thing, but it’s how we translate.

JB: For us the moon is this essential piece of how you can rationalize your own existence. Drawing from that as a human seems like trying to dig back into being a caveman. For us, it’s that way in which producing a piece of art, in and of itself, is a method of mythologizing a thing. It puts it through our filter and exports it. The materials themselves in the moon skins, they are mimicking materials. Silicone is mimicking the properties of silicon, and then we also use regolith simulant—regolith means rock blanket.

SB: It’s dirt that can’t support life.

JB: A similar material to regolith is slag which we use a lot of. It is a byproduct of the production of burning coal.

SB: It looks almost identical to regolith.

Are there parts in your practice that one of you will take a back seat?

SB: It really depends per project. We have a rule where we do whatever we want. It’s kind of a weird rule, but when we got out of grad school we were having a really difficult time. We both absolutely loved grad school, but the problem we had was we would get excited about an idea and start to talk about it and the first thing others would want to do is critique. It would kill our ideas. Instead of us just starting something and see where it goes, we would abandon our idea. When we got out of school we were doing the same thing with each other. We were using the worst word in the world which is problematic. That word does not exist to us anymore. Now our rule is that when one of us has an idea—we do it and we see what happens. And we play and we play and we play, and if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. But we don’t make each other feel like crap and abandon things. Every work that we’ve done is one of our original ideas, but it’s morphed so much that we don’t necessarily always know who did it.

JB: It’s to the point where if you are in such constant dialogue with one other person, and literally everything you experience that other person experiences as well. It is really hard to place the point of origin of any singular thing.

SB: Some things we will do together in unison, sometimes if multiple things need to happen we will split up.

JB: We still express our skill sets separately.

SB: Sometimes we will carve a rock together and if the rock is too small, one person will take it over and the other person will do something else. It all depends per piece. Just using our strengths. Anything we do that is photo or video-based we do that together. When it comes to sculpture, it just depends.

Why didn’t you guys start collaborating until you got married?

SB: It was actually at the same time. We have been together for almost ten years now and for the first five years that we were together, we were each other’s studio assistants in a way. If he had a project, I helped, if I had a project, he helped. We didn’t really ever talk conceptually, we just helped each other. All of my work was really dark and then my father passed away and I couldn’t do it anymore. Joseph was in grad school and I helped him with a couple of projects. We figured out we liked working together, but everything including our language and aesthetic was different. Completely night and day. We decided to talk about collaborating. I felt like I was a wreck, I was trying these weird projects and they weren’t clicking for me. So we kind of just talked and I decided to apply for grad school and if I got in we were going to work together for one year and see what happens. I got in, and then we started working together.

JB: Essentially, for whatever reason, we both offset the thing that had previously upset ourselves about our own work.

SB: It was a teaching experience for both of us. I would consider him the best teacher I’ve had.

JB: When I work with you now, the thing that used to bother me about my work when I was on my own, isn’t there.

SB: We both have our weaknesses. He is really erratic and crazy and all over the place, and I am really anal and I have an attention to detail, and he doesn’t in this other sort of way. We are still very similar to who we were. I know that if we ever stopped working together, I have become so much stronger by working with him. I am constantly learning and not shutting myself off. We are both growing on our own.

Explain your obsession with outer space.

SB: We had this beautiful harvest moon two falls ago that we started staring at, and also reading this book called “The Sun’s Heartbeat,” which is one of the most magical books you will ever read. The guy who writes it is in love with the sun. When I read about how he described a total eclipse of the sun, what it looked like and how he felt, I was crying reading it. It was so beautiful. So between those two things. Those are two of the things humans can really see. When you are outside and you just see what is in front of you, it is very easy to forget that we are on this circular-esque thing flying around.

JB: Our earth orbits, because of gravity we do not experience it, but our earth orbits at like 1,300 miles per hours.

SB: And then our galaxy is flying too. Everything is moving. It’s almost impossible for a person to fathom that.

JB: You start to think about that, and then you feel the weight on your feet right now. That is the force of you being sucked to the center of the planet!

For us the moon is this essential piece of how you can rationalize your own existence. Drawing from that as a human seems like trying to dig back into being a caveman.

When was the first time you touched a meteorite?

SB: When we went to New York last fall we went to the Hayden Planetarium. We both hugged it. It was huge, gorgeous. The meteorites we get, we get from a guy in Alaska, our meteorite guy. He’s a geologist and an astronomer and collects and sells meteorites. He’s awesome because he is so isolated that when you call him he will just talk to you for hours. He is so cool. Joseph gave me my first meteorite last year for Christmas.

JB: That one fell in Siberia in 1947.

SB: These are older than our planet!

JB: That is from space!