Inside\Within is a constantly updating web archive devoted to physically exploring the creative spaces of Chicago's emerging and established artists.

Support for this project was provided by The Propeller Fund, a joint administrated grant from Threewalls and Gallery 400 at The University of Illinois at Chicago.

Search using the field below:

Or display posts from these tags:

3D printing 3D scanning 65 Grand 7/3 Split 8550 Ohio 96 ACRES A+D Gallery ACRE animation Art Institute of Chicago Arts Incubator Arts of Life audio blogging Brain Frame CAKE Carrie Secrist Gallery casting ceramics Chicago Artist Writers Chicago Artists Coalition Chicago Cultural Center Cleve Carney Art Gallery Clutch Gallery Cobalt Studio Coco River Fudge Street collage collection Columbia College Chicago Comfort Station comics conceptual art Contemporary Art Daily Corbett vs. Dempsey Creative Capital DCASE DePaul University design Devening Projects digital art Dock 6 Document drawing Duke University dye Elmhurst Art Museum EXPO Chicago Faber&Faber fashion fiber Field Museum film found objects GIF Graham Foundation graphic design Harold Washington College Hatch Hyde Park Art Center illustration Image File Press Imagists Important Projects ink installation International Museum of Surgical Science Iran Jane-Addams Hull House Museum jewelry Joan Flasch Artist's Book Collection Johalla Projects Julius Caesar Kavi Gupta Links Hall Lloyd Dobler LVL3 Mana Contemporary metalwork Millennium Park Minneapolis College of Art and Design Monique Meloche Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) National Resources Defense Council New Capital Northeastern Illinois University Northwestern University Ox-Bow painting paper mache Peanut Gallery peformance Peregrine Program performance photography PLHK poetry portraiture printmaking public art Public Collectors publications Renaissance Society risograph rituals Roman Susan Roots&Culture SAIC screen printing sculpture Sector 2337 Shane Campbell Silver Galleon Press Skowhegan Slow Smart Museum Soberscove Press social practice South of the Tracks Storefront SUB-MISSION Tan n' Loose Temporary Services Terrain Terrain Biennial text-based textile textiles The Banff Centre The Bindery Projects The Cultural Center The Franklin The Hills The Luminary The Packing Plant The Poetry Foundation The Poor Farm The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Threewalls Tracers Trinity College Trubble Club University of Chicago University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) University of South Florida at Tampa Valerie Carberry Vermont Studio Center video weaving Western Exhibitions wood carving woodwork Yellow Book Yollocalli Arts Reach zinesInside\Within is produced in Chicago, IL.

Get in touch:

contactinsidewithin@gmail.com

Zoe Nelson: The Reverse of the Reverse

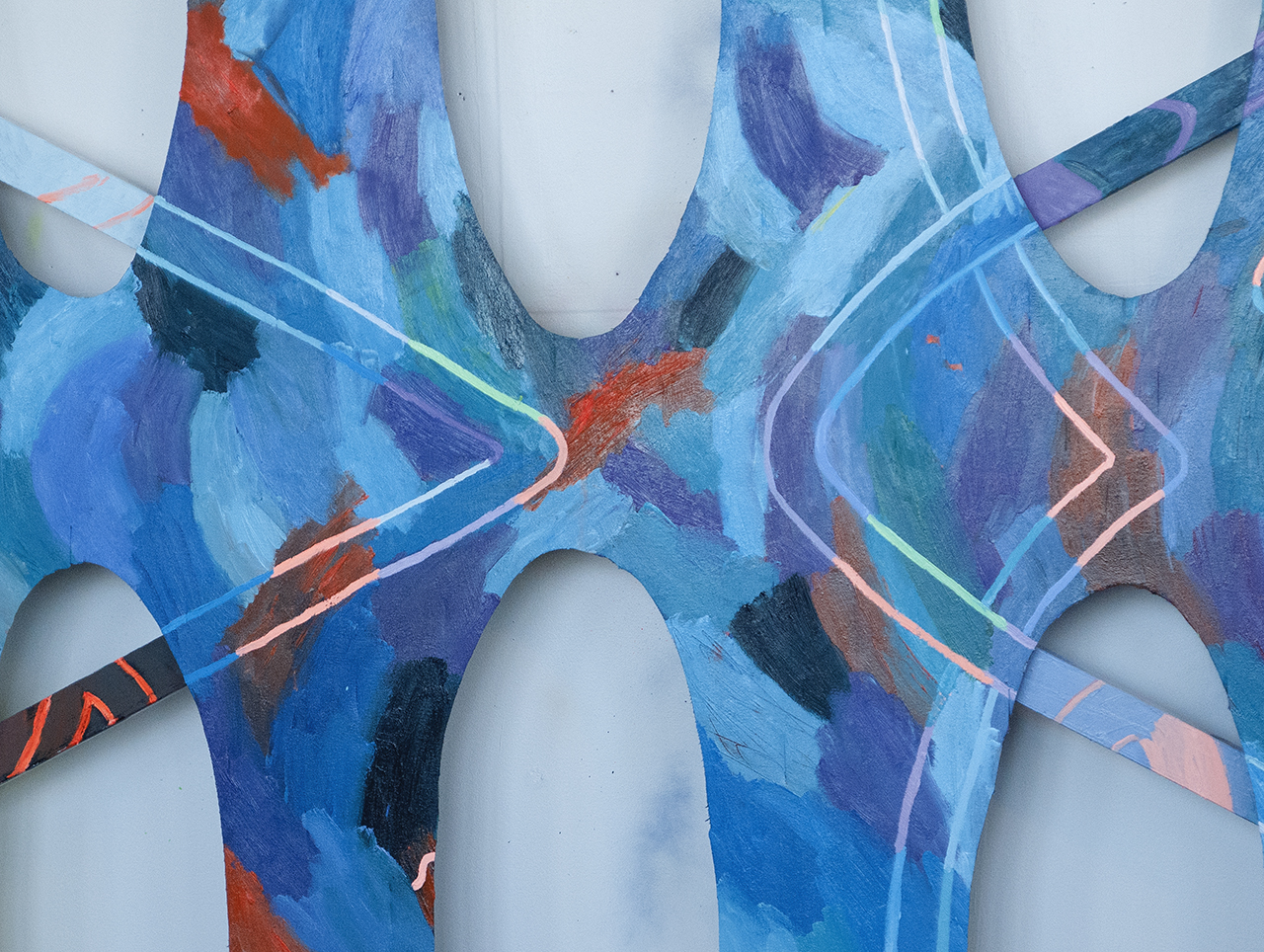

Giving equal thought to both the front and back of the canvas, Zoe has reclassified the sides of her work as “recto” and “verso.” This strategic retitling allows Zoe to democratize the way she views, speaks, and applies paint to the surface of the canvas, attempting to destabilize the hierarchy between front and back. Zoe slices holes into the canvas to expose its inner structure, leaving these open spaces as pauses or portals into more loaded psychological spaces.

I\W: How has your work gradually become more minimal?

ZN: There was a year between finishing grad school in New York at Columbia University and moving here in 2010—a year of processing. I started a series of abstract paintings that were about deconstructing the canvas, but I hadn’t yet cut into it. When I moved to Chicago I understood that the next step was actually to make that move and cut into the canvas, which opened up a set of questions about the “inside” of a painting. That takes me to 2011 where I was really exploring that inside and seeing how much I could cut away and still have a painting, and then assembling pieces back onto it. Sometimes I would slice into or through the frame, and the painting would move more into sculpture and/or would actually fall apart completely. In 2012 I had a show at Lloyd Dobler. I was thinking about the back of the canvas and about the painting as an object. There is a hallway in the space and I had the idea to make a walk-through painting that would be nestled between the two walls of the hallway and also be site-specific. In order to see the other side you had to walk through the large cut which opened up as an investigation about the relationship of the work to the viewer’s body and the painting as object or as an architectural intervention. From there I started to think about how my work could hang in free space and how both sides of the painting could be prioritized surfaces to engage with. That leads to the double-sided paintings, a couple of which I had at Western Exhibitions in 2013, and then most recently all of the paintings at Cleve Carney Art Gallery were double-sided.

How are both the frame and cross-braces integral aspects of your paintings?

The cuts and cross-braces are composed in response to one another, and the first step of starting a painting is sketching out a design for both. At the beginning, I am mostly thinking about creating movement between the cross-braces peeking through the cuts and the canvas’s surface. I refer to the sides of these paintings as recto (front) and verso (back). Recently, I have been thinking a lot about the relationship between the two sides, and how to use cuts and cross-braces to create movement between both sides. The recto side of the painting often relies more on colorful painterly surfaces, while the verso side engages with the sculptural shape of the cross-braces. Sometimes both sides have a direct relationship and pull forms or colors from each other, and other times the sides come from very different headspaces.

What sort of psychological space do you enter for each work? How do you classify that space while building the painting?

My background is figurative, and I arrived at painting through an interest in the body and people, but mostly my interest was with psychological spaces. There was a point in grad school when I realized that the spaces that I was most interested in were spaces that could not be articulated, or were not representational spaces. They were were liminal, shifting, and temporal spaces. At this point I removed the figure from the canvas, and became very interested in how to articulate psychological and emotive states, or one’s shifting perception of self. When I start a new painting, in addition to thinking about movement and the painting as object, I also think about what sort of emotive or psychological space I want to evoke by the cuts in a painting. The number, scale, shape and composition of cuts all play a large part both formally and psychologically in a painting. A painting that feels very playful and open with two cuts, may provoke feelings of anxiety or loss with seven cuts. Then, when I start to think about color, I am already thinking about color in relationship to the negative spaces in the painting. Perhaps the color scheme will accentuate a feeling of anxiety in a painting, or alternatively, the color may introduce a new feeling or psychological mindset, so that these two experiences—for example anxiety and openness—co-exist.

How do you view these empty areas that allow you to see through to the other side? Do you feel as if they are simply pauses within the work?

When I think of a pause, I think of a place for the eye or self to rest for a moment. Sometimes the shallow cuts are pauses, but many times the holes function more as loaded psychological spaces, than as comfortable resting points. The metaphor of the elephant in the room is apt. It is precisely because of the elephant’s invisibility (the fact that it cannot be seen or spoken about), that it gains its power. By being both present and absent they define a lot of what is around them. Since the paintings are double-sided and hang in space, the holes also often function as a passageway between both sides as well as between the painting and actual gallery space. Whether or not one is “inside” or “outside” of a painting is contingent on one’s subjective perspective, and shifts as people walk around the space. From where I stand in the gallery, I might see someone’s nose momentarily framed by a cut in a painting, and therefore it looks to me like the other person is inside the painting. But from where they stand, the situation might be in reverse, or perhaps they cannot even see me at all in that moment. I am very interested in how an installation like this opens up the parameters of what is and is not part of the painting, and in so doing queers gendered binaries such as front/back, inside/outside, and subject/object. The hole itself has such a strong gendered connotation in Western society, as the inverted phallus or heteronormative metonym for cis-gendered “woman.” Through creating double-sided paintings that often have not one or two but many holes, I am interested in challenging the limited binary understanding of a hole as the “other,” and inviting more expansive, fluid experiences.

The hole itself has such a strong gendered connotation in Western society, as the inverted phallus or heteronormative metonym for cis-gendered “woman.” Through creating double-sided paintings that often have not one or two but many holes, I am interested in challenging the limited binary understanding of a hole as the “other,” and inviting more expansive, fluid experiences.

Do you feel as if the holes within your works are a way to collaborate with the bodies and and objects that are seen within the painting’s absences in a space?

I started thinking about different ways for viewers to engage with the holes in 2012 when I did the installation at Llyod Dobler. There it was more of an invitation to walk through the painting and momentarily be inside the painting. In fall 2014 I did a window display at Roots&Culture. For that piece I hung three paintings against the glass window with mirrors installed on a wall a couple of feet behind them. From the street, you could see the front of each painting, the back of each painting, and surrounding environment reflected in the mirror, and depending on where you stood, your own gaze reflected as well. I was very interested in how that installation situated one’s gaze between the inside/outside of the gallery and each painting. I had been thinking about doing an installation of all double-sided work hung from the ceiling precisely so the viewer would become a part of the work and the boundaries of the paintings would blur as one walked through the space. I was waiting for the right space and then Cleve Carney came along.

How did you hang the work to specifically interact with the provided space?

While I was making paintings for the Cleve Carney Art Gallery, I was thinking about ways of installing the work that would intervene with the white cube space of the gallery. I knew that I wanted all of the work to be double-sided, and mostly hung from the ceiling, so that viewers would be encouraged to walk around the space in different patterns, with no clear beginning or end point. I decided to hang one painting about 13 feet above the ground and perpendicular to the wall to push against the wall and ceiling, and one of the other paintings was hung at an angle neither parallel nor perpendicular to the rest. Depending on where you stood, you would see a combination of recto and verso sides, and given the double-sidedness of each painting, you could never see both sides at once. I was thinking about the viewer as a very active participant, with myriad possibilities of looking and walking. Since I had been thinking a lot about viewers’ bodies and different walking patterns in relation to the work, about a year ago I starting thinking about the idea of incorporating choreographed movement. I had seen a performance by the Leopold Group, and although I do not know very much about dance, I started a conversation with the choreographer, Lizzie Leopold, about the possibility of her composing dance to be performed around an installation of my work. The show at the Cleve Carney gallery seemed like the perfect space to explore adding dance, and the Leopold Group did three performances in the space over the course of the show. The dance was set to a clip from William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, and referenced reoccurring shapes found in some of my paintings. The audience was invited to walk around the full space of the gallery during the performance, blurring the lines between viewer, performer, and installation.

I noticed many of your works have spray paint on the verso side. Do you have the intention of dividing up the material you use depending on the side of the work?

I started spray painting when I was at Ox-Bow in the fall of 2014 thanks to a suggestion by Sabina Ott. I had been struggling with how to engage with the verso sides in a meaningful way, that was still different from the recto sides. Before Ox-Bow, I had been treating both sides very similarly. My initial impulse to treat both sides the same came from a feminist desire to destabilize the hierarchy of front over back. However, not only was it annoying to have to gesso both sides of the canvas, I felt like the works got visually very heavy with so much paint on both sides, which was the opposite effect that I was going for. Starting to spray paint on the back allowed me to engage with the verso side in a much lighter and faster way that suited my needs, and after all, there can be equality through sameness and equality through difference.